How to Design Large Programs with Abstraction and Encapsulation

I spend a lot of time as a professional coder working on very large programs, attempting to grow them while also keeping them from collapsing under their own weight. This is hard.

Abstraction and Encapsulation

The Challenge

A large program has a lot of behavior to specify. The complexity of the behavior specified by a program is roughly proportional to its size.1

However a coder, being only human, can only hold a fixed amount of concepts in their head at once.

Chunking

The number of concepts can be reduced by chunking them into larger concepts that are less numerous. For example a bundle of lines can be chunked into a single function or a method.

Chunking allows you to reduce the total number of concepts that you need to keep in your head at once.

There are many kind of chunks. The kinds I normally think about are:

- Lines

- Paragraphs

- Functions, Methods2

- Classes

- Modules3

- Packages4

- Assemblies, Libraries

- Binaries

- Services

Abstractions

A larger unit that is created by bundling smaller units is called an abstraction. An abstraction typically has:

- a name

- a public surface area, and

- a private interior.

For a function unit, it has a function name, some number of parameters and a return value which serves as the public surface area, and a body of code lines which serve as the private interior.

Encapsulation

An abstraction reduces global complexity by hiding (or encapsulating) its large private interior, exposing only the smaller public surface area to the rest of the system. One only needs to understand the smaller public surface area when using the function and not the details of the private interior.

A well-designed abstraction thus strives to minimize its public surface area while maximizing its private interior.5 Such an abstraction takes up only small mental space relative to its interior complexity.

As an example of minimizing public surface area, let’s consider the example of a larger kind of unit, a class:

By extension of the principle above, everything should be private by default; only those methods that need to be public (because they are used externally) should be made public.

If a method on a class is declared public when it is only used internally, you can perform a Refactor Privatize to make it private.

The same principle applies yet again to modules, a larger kind of unit:

Again, everything should be private by default.

Combining Encapsulated Abstractions

Encapsulated abstractions really shine in reducing program complexity when you combine them together.

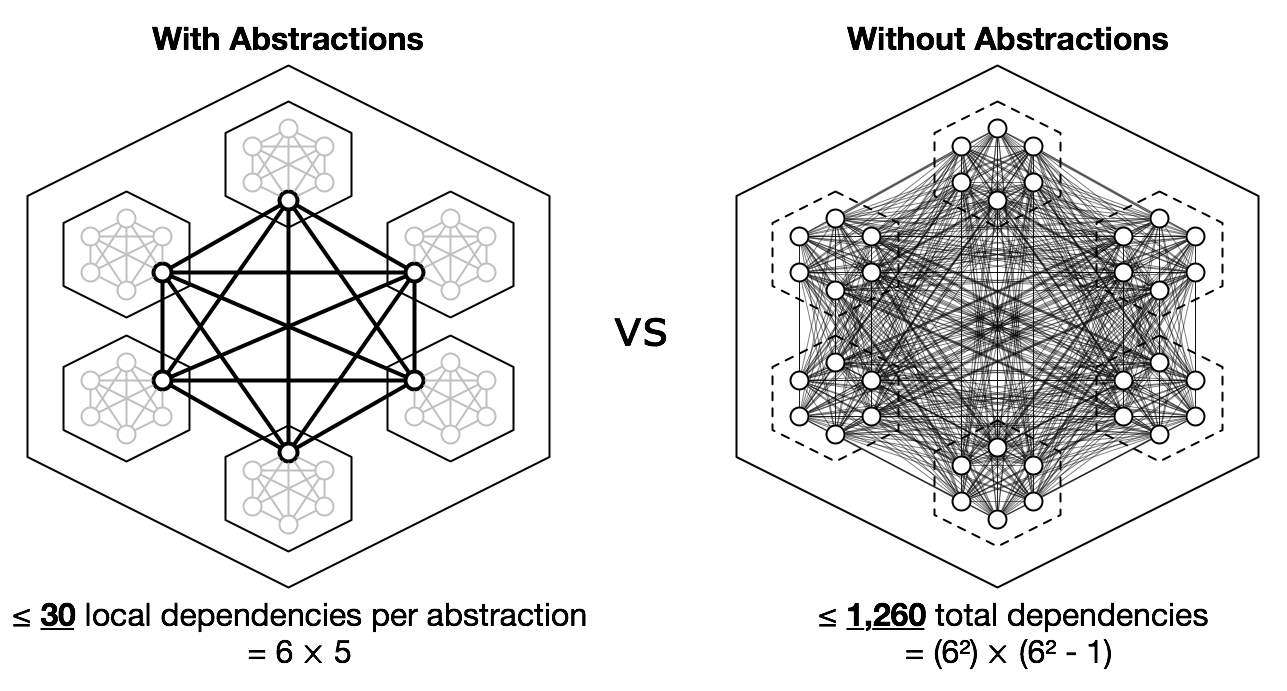

Without abstractions everything can depend on everything else which creates a potential combinatorial explosion of complexity. By contrast with abstractions, the local complexity is bounded much more tightly.

Within an abstraction the maximum local complexity is proportional to the size of that particular abstraction’s private interior plus the size of the public surface areas of all other abstractions.

Names Matter

It is worth noting that a name by itself serves as an kind of abstraction. A good function name can tell you what the function does without you needing to crack it open and read its implementation. A good class name tells you what it represents, what it is responsible for, what it is, and what it is not.

If you have to look behind a name to figure out what something does, the name needs to be improved via a Refactor Rename. Refactor Rename is probably the most common refactoring I apply out of all the kinds of refactorings I use.

For simple names, coding conventions related to names often can tell you a lot. For example:

- Methods:

setFoo- Sets the “foo” property on a class. Take a single value as a parameter and returns nothing.getFoo- Gets the “foo” property on a class. Takes no parameters and returns the value.initFoo,setupFoo- Designed to be called once.updateFoo- Designed to be called multiple times.

- Variables

curFoo- The current element when iterating over a collection of foos.i,j,k- An uninteresting loop counter.e,f- An uninteresting exception or event.minFoo,maxFoo- A minimum or maximum permissive value for foo, inclusive.limFoo- A maximum permissive value for foo, exclusive.fooIndex- A 0-based position of something.fooOrdinal- A 1-based position of something.LOUD_CASE- A constant.

To Be Continued

I’ve got many other techniques for designing large programs. In future articles I hope to share some of these with you.

-

I’m intentionally oversimplifying: Program complexity actually tends to grow with the square of its size rather than linearly because all pieces of the program can depend on the other pieces and these dependencies contribute to the program complexity.↩

-

A method is kind of function that is attached to a class.↩

-

A module contains functions, classes, and variables, among other things.↩

-

A package is a module that contains submodules.↩

-

A Philosophy of Software Design makes the same recommendation under the guidance “Modules should be deep”, where a “deep module” is an abstraction whose public surface area is small compared to the volume of its private interior.↩