Bulkheads: A pattern for handling unexpected errors in software

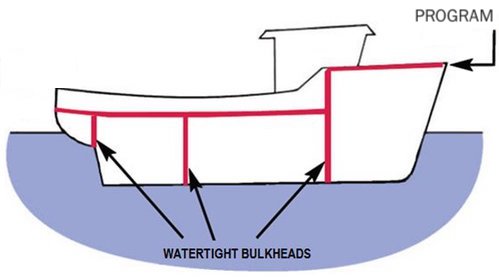

Some seafaring ships divide their body into multiple watertight compartments, so that if one compartment becomes flooded the rest of the ship will remain floodfree and intact. I got the idea of using a similar pattern of “bulkheads” in software to limit the damage caused by an unhandled exception.

Normally an unhandled exception will cause its thread to print diagnostic information to the console and then stop. This is an acceptable error-handling strategy for many command-line programs, but it is not a good error-handling strategy for a graphical program where the console is invisible.

Goals

I’ve been working on a graphical program where I want all exceptions and errors to be reported to the user in some way, rather than failing silently and presenting an unresponsive user interface when something goes wrong.

Additionally, there are certain critical sections of the program where an unhandled exception could leave a nearby data structure in an invalid state, causing subsequent operations on that structure to fail and/or propagate the corruption to other parts of the program state. It would be better if an unhandled exception occurring in a critical section marked any affected data structures as corrupt, such that further operations attempting to access those structures would refuse to run.

The Bulkheads Pattern can be used to meet both of those goals:

How it Works

I’ve implemented a family of @capture_crashes_to... function decorators in Python which mark a critical section of code and define which Bulkhead the critical section is related to.

Any exception raised in the critical section which bubbles up to the decorator will be caught at the last moment and set as the crash_reason for the associated bulkhead.

If a function calls into a critical section marked with @capture_crashes_to... whose bulkhead has been marked as crashed, the critical section will refuse to run and will instead return to the caller immediately, possibly returning a default value.

Example

Below, the child_task_did_complete listener method is marked with @capture_crashes_to_self, so any unexpected exception raised inside the listener won’t escape and crash the thread which called the listener. Instead the exception will be stored in the Task’s crash_reason.

class Task(Bulkhead):

crash_reason: Optional[BaseException] = None

class DownloadResourceTask(Task):

@capture_crashes_to_self

def child_task_did_complete(self, task: Task) -> None:

if task is self._download_body_task:

...

elif task is self._parse_links_task:

links = self._parse_links_task.future.result()

embedded_resources = [

Resource(

self._resource.project,

urljoin(self._resource.url, link.relative_url))

for link in links if not link.embedded

]

for resource in embedded_resources:

self.append_child(resource.create_download_task(...))

else:

...

And indeed an unhandled exception did end up getting raised in the above code: The urljoin operation was observed to raise an unexpected exception for certain unusual inputs even though it generally never raises.

Try it!

The infrastructure for using bulkheads currently lives as a utility module in the Crystal project. You can install it to your local Python virtual environment using:

python -m pip install crystal-web

Here is a small program you can run in the Python REPL that demonstrates the use of bulkheads:

>>> from crystal.util.bulkheads import BulkheadCell, capture_crashes_to

>>>

>>> divide_bulkhead = BulkheadCell()

>>>

>>> @capture_crashes_to(divide_bulkhead)

... def divide(x, y):

... return x / y

...

>>> print(divide(10, 2))

5.0

>>> print(divide(10, 0))

Exception in bulkhead:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "/Users/me/Projects/crystal-web/crystal/util/bulkheads.py", line 292, in bulkhead_call

return func(*args, **kwargs) # cr-traceback: ignore

File "<stdin>", line 3, in divide

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

None

>>> divide_bulkhead.crash_reason

ZeroDivisionError('division by zero')

>>> print(divide(10, 5))

None

See the API for more detailed information about how to use bulkheads.

Appendix

Effective Critical Sections and Bulkheads

For critical sections, I’ve found it effective to protect:

- listener methods, since they usually operate in a different conceptual context than their caller, and it is useful to prevent crashes inside listeners from also crashing their callers;

- the run function in new threads, which can capture any exception that is about to crash the thread; and

- the main function in the main thread, which can capture any exception that is about to crash the thread.

For bulkheads, I’ve found it effective to protect:

- Component structures1 (which can be arranged in a tree, forming a larger Composite structure),

- certain “top-level” structures2 in the program

Enforcing that an error-handling strategy is defined

It can be useful for a caller to enforce that a callee has an explicitly defined error-handling strategy (via a @capture_crashes_to* decorator). For example, a function that is dispatching events to listeners may want to enforce that each listener is marked with @capture_crashes_to* before calling it. Such enforcement can be implemented with the following utilities:

run_bulkhead_call(func)– Calls a function after verifying it is marked with@capture_crashes_to*. Raises if the function is not marked.ensure_is_bulkhead_call(func)– Raises if the specified function is not marked with@capture_crashes_to*.is_bulkhead_call(func)– Returns whether the specified function is marked with@capture_crashes_to*.

Example of an event dispatcher which enforces its listeners are marked with @capture_crashes_to*:

def _resource_did_instantiate(self, resource: Resource) -> None:

for lis in self.listeners:

run_bulkhead_call(lis.resource_did_instantiate, resource)

See API > Error-handling enforcement utilities for more information.

API

Everything in this section is imported from crystal.util.bulkheads. For example:

from crystal.util.bulkheads import Bulkhead, capture_crashes_to_stderr

Bulkhead API

First, define locations where unhandled exceptions can be captured to by implementing the Bulkhead protocol:

class Bulkhead(Protocol): # abstract

"""

A sink for unhandled exceptions (i.e. crashes).

"""

crash_reason: Optional[CrashReason]

CrashReason = BaseException

Or if you don’t want to implement your own bulkhead type, you can use the included BulkheadCell:

class BulkheadCell(Bulkhead):

"""

A concrete Bulkhead which stores any crash that occurs,

but takes no special action to report such crashes.

"""

crash_reason: Optional[CrashReason]

def __init__(self, value: Optional[CrashReason]=None) -> None:

self.crash_reason = value

Critical Section API

Then, mark critical sections in your code with an appropriate @capture_crashes_to* decorator. There are several to choose from:

- For critical sections defined as a method on a sensitive data structure that is its own bulkhead,

@capture_crashes_to_selfis a good choice:

def capture_crashes_to_self(

bulkhead_method: Optional[Callable[Concatenate[_B, _P], _RT]]=None,

*, return_if_crashed=None # _RF

):

"""

A Bulkhead method that captures any raised exceptions to itself,

as the "crash reason" of the bulkhead.

If the bulkhead was already crashed (with a non-None "crash reason") then

this method will immediately abort, returning `return_if_crashed`.

Examples:

class MyBulkhead(Bulkhead):

@capture_crashes_to_self

def foo_did_bar(self) -> None:

...

@capture_crashes_to_self(return_if_crashed=Ellipsis)

def calculate_foo(self) -> Result:

...

"""

- For critical sections defined as a method which takes a sensitive data structure (i.e. a bulkhead) as an argument,

@capture_crashes_to_bulkhead_argis a good choice:

def capture_crashes_to_bulkhead_arg(

method: Optional[Callable[Concatenate[_S, _B, _P], _RT]]=None,

*, return_if_crashed=None # _RF

):

"""

A method that captures any raised exceptions to its first Bulkhead argument,

as the "crash reason" of the bulkhead.

If the bulkhead was already crashed (with a non-None "crash reason") then

this method will immediately abort, returning `return_if_crashed`.

Examples:

class MyClass:

@capture_crashes_to_bulkhead_arg

def other_foo_did_bar(self, other: Bulkhead) -> None:

...

@capture_crashes_to_bulkhead_arg(return_if_crashed=Ellipsis)

def calculate_baz(self, other: Bulkhead) -> Result:

...

"""

- Sometimes you may have an outer function that is already operating on a sensitive data structure (i.e. a bulkhead) which wants to define (and call) an inner function that also operates on the same structure. In that case it may be useful to protect the inner function with

@capture_crashes_to(bulkhead), specifying the bulkhead to use at the time of decoration:

def capture_crashes_to(

bulkhead: Bulkhead,

return_if_crashed=None # _RF

) -> Callable[[Callable[_P, _RT]], Callable[_P, Union[_RT, _RF]]]:

"""

A method that captures any raised exceptions to the specified Bulkhead,

as the "crash reason" of the bulkhead.

If the bulkhead was already crashed (with a non-None "crash reason") then

this method will immediately abort, returning `return_if_crashed`.

Examples:

@capture_crashes_to(bulkhead)

def foo_did_bar() -> None:

...

@capture_crashes_to(bulkhead, return_if_crashed=Ellipsis)

def calculate_foo() -> Result:

...

"""

- As a last resort, you may have a critical section where there is no reasonable bulkhead available to route an unhandled exception to. For example if your core error reporting infrastructure code (like a

display_errorfunction) fails, the only reasonable choice may be to fallback to printing the exception to the standard error stream (stderr):

def capture_crashes_to_stderr(

func: Optional[Callable[_P, _RT]]=None,

*, return_if_crashed=None # _RF

):

"""

A method that captures any raised exceptions, and prints them to stderr.

Examples:

@capture_crashes_to_stderr

def foo(self) -> None:

...

@capture_crashes_to_stderr(return_if_crashed=Ellipsis)

def calculate_foo(self) -> Result:

...

"""

Critical Sections (in Crystal) always print to the standard error stream

The current implementation of the @capture_crashes_to* decorators in Crystal always prints unhandled exceptions to stderr as a side effect, to indicate that a crash happened.

- Most of the decorators print in yellow warning text because the crash was presumably handled when it was routed to a bulkhead.

- However the

@capture_crashes_to_stderrdecorator prints in red error text to signal that the only handling of the crash was to print it tostderr.

In the future, if/when the bulkheads.py module is extracted to its own package on PyPI, independent of Crystal, I expect I’ll alter the @capture_crashes_to* decorators to NOT print anything to stderr by default since I don’t think that side-effect is appropriate for all programs that may want to use these decorators.

Error-handling enforcement utilities

def run_bulkhead_call(

bulkhead_call: Callable[_P, _R],

/, *args: _P.args,

**kwargs: _P.kwargs

) -> '_R':

"""

Calls a function marked as @capture_crashes_to*,

which does not reraise exceptions from its interior.

Raises AssertionError if the specified function is not actually

marked with @capture_crashes_to*.

"""

def ensure_is_bulkhead_call(callable: Callable) -> None:

"""

Raises AssertionError if the specified function is not actually

marked with @capture_crashes_to*.

"""

def is_bulkhead_call(callable: Callable) -> bool:

"""

Returns whether the specified function is marked with @capture_crashes_to*.

"""

-

Component bulkhead structures in my website downloader Crystal include (1)

Task(which compose to form the Task Tree) and (2)entitytree.Node(which compose to form the Entity Tree)↩ -

Top-level bulkhead structures in my website downloader Crystal include (1) the Task Scheduler itself (by using the root

Taskas the associated bulkhead), (2) the Task Tree UI (by again using the rootTaskas the associated bulkhead), and (3) the Entity Tree UI (which is its own bulkhead that reports errors to the Task Tree UI).↩