Error Handling

Most of the time programs operate happily inside their main scenario. Occasionally they need to cope with unusual circumstances, such as being no longer able to read data from the network because the user has turned off their WiFi. The process by which a program responds to an error is called error handling.

- Behaviors Upon Failure

- Reporting Errors

- Error Seriousness

- Guarantees after Failure

- Failing Fast (and Error Locality)

- Implementation Considerations for Exceptions

- Summary

Behaviors Upon Failure

At the time an error occurs in a function there are a few things it can do:

- Delegate to its caller

- Typically a function doesn’t have enough information to decide how to handle the error itself. In such a case the error is reported to the calling function, which is typically higher-level and has more context.

- For example if an I/O error occurs while parsing data from a file, the parser will typically just report the I/O error to the code that invoked the parser. The parser itself only knows how to parse things and not what should be done in the case of an I/O error.

The particular error handling strategy of a function reporting an error to its caller is so common that many programming languages provide special mechanisms to support it, particularly in the form of exceptions.

- Display the error to the user and continue

- This is a common pattern for routine errors in interactive programs.

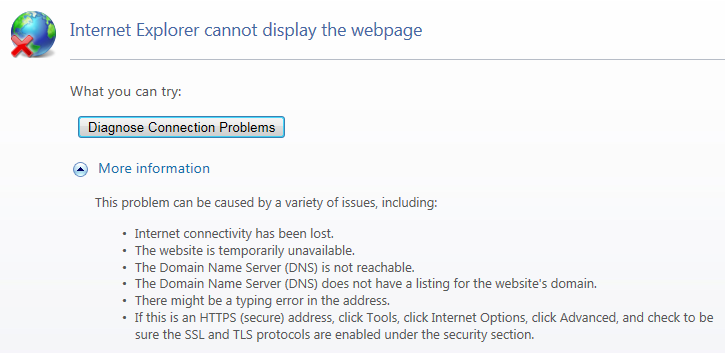

For example a web browser that cannot access a particular webpage will display an error page explaining why the page could not be accessed.

- Display the error to the user and exit

- This is a common pattern for unexpected errors in contexts where total program failure is deemed acceptable.

- In languages that use exceptions, any unhandled exceptions that bubble out of the main function or to the initial function in a thread will terminate the program or the thread. Programs can avoid this fate by adding a top-level exception handler that takes alternate action.

- Examples:

- In PHP it is an idiom to use the

die()function upon the failure of many operations:$connection = mysql_connect('localhost', 'dbuser', 'password') or die('Could not connect to MySQL server.');

The Linux kernel makes great use of the

panic()function when it gets into a bad state, stopping the entire operation of the computer.

- In PHP it is an idiom to use the

- Log the error and continue

- This is a common pattern for non-interactive programs and programs that need to keep running continuously, such as web servers.

Naturally there needs to be somebody who goes through the log occasionally to look for problems if this error handling strategy is used.

- Ignore the error implicitly and continue blindly

- This is almost always done out of laziness.

In C, this just means ignoring the result of a function that returns an error code.

- Ignore the error explicitly and continue boldly

- This is usually done out of laziness.

- One legitimate case when this is done is ignoring I/O errors when closing a resource during cleanup, since there isn’t anything sensible that can be done at that point. A Java example:

r = new Resource(); try { ... } finally { try { r.close(); } catch (IOException e) { // ignore } }

Less common handling strategies include:

- Prompt the user to decide what to do

- Attempt recovery and retry (or resume) the original operation, perhaps with different inputs

Reporting Errors

When a function wants to report an error, it has to pass information about the error to its caller. There are a few ways that error information can be encapsulated:

- Error Codes

- When a function is designed to report errors using error codes, it is declared to return an integer or other integer alias (ex:

OSErr). Upon success the function returns 0 (ornoErr). Upon failure the function returns some other value that describes the type of error encountered. Should the function need to return other values upon success it must declare out parameters to pass them back to the caller. - Error codes have several disadvantages that make their use uncommon in modern high level languages:

- An error code only describes the type of error encountered, but not any additional contextual information that would be useful in handling the error. Typically only the function that is one hop away from the error site has enough additional context to actually handle the error nicely.

- For example if you try to open a nonexistent file on classic Mac OS, you’ll get back the error code

fnfErrwhich indicates that the specified file was not found. Note however that this error code alone doesn’t include information about which file couldn’t be found, which is necessary context to display a meaningful error message.

- For example if you try to open a nonexistent file on classic Mac OS, you’ll get back the error code

- A function that uses error codes relies on its caller to check whether it returns an error. Lazy callers might not actually check, causing any reported errors to be ignored silently.

- For example I have never seen a C program actually check the result of

printf(), even though it can return an error code upon I/O error. This behavior is reasonable in this case because there isn’t much a program can do to alert the user if it can’t print to the screen. - More problematic are C programs that fail to check the result of

malloc()forNULLwhen allocating objects. Such programs will crash whenmallocreturnsNULLduring an out-of-memory condition and the caller tries to manipulate it.

- For example I have never seen a C program actually check the result of

- When an error code occupies the return value of a function, that return value can’t be used for “normal” function output. This typically means that multiple functions returning error codes cannot be chained together on the same line, increasing verbosity.

- An error code only describes the type of error encountered, but not any additional contextual information that would be useful in handling the error. Typically only the function that is one hop away from the error site has enough additional context to actually handle the error nicely.

- The one advantage of error codes is that they are very fast to create and return, improving performance in fragments of code that experience a large number of errors. However this performance-over-usability tradeoff is almost never worth it in modern programs.

These days error codes are only used commonly in programming languages like C that don’t support the use of exceptions.

- When a function is designed to report errors using error codes, it is declared to return an integer or other integer alias (ex:

- Error Sentinels (such as

null,-1, or0)- A function that reports errors using error sentinels uses its return value to return the normal output of the function most of the time. However when an error occurs, a special invalid1 value (a sentinel) is returned instead.

- For example if you

read()from anInputStreamin Java, usually the resultant byte value is returned. But if the end-of-file is reached, the special value of-1is returned instead.

- For example if you

- Error sentinels suffer from the same disadvantages as error codes. And they have the same performance advantage.

- Unfortunately the use of error sentinels, especially

null, remains common in many modern programs despite their disadvantages. Even in cases where a Null Object could be used to better effect. Some statically typed languages like Haskell and SML explicitly represent the potential of a sentinel being returned using a datatype such as

MaybeorOption. Typically this is done so that the compiler can automatically flag callers that aren’t checking for sentinels properly, eliminating their largest disadvantage.

- A function that reports errors using error sentinels uses its return value to return the normal output of the function most of the time. However when an error occurs, a special invalid1 value (a sentinel) is returned instead.

- Exceptions

- An exception is an object that encapsulates information about an error. This includes not only the type of error but also additional contextual information that can be used to generate a reasonable error message and assist in debugging by an end-user or developer.

- Exceptions also typically include a stack trace which can be used to pinpoint the location in the program where the error occurred originally, which is valuable for debugging.

- Some languages like Java and Python provide exception chaining (or wrapping), which is special support for higher-level exceptions to reference any lower-level exceptions that caused the higher-level exception to occur.

- A function that uses exceptions for error reporting can throw (or raise) an exception when an error occurs. When this happens the runtime looks for an enclosing exception handler that knows how to deal with the exception. If it finds a handler the handler is run. If no such handler is found the function terminates and the same exception is rethrown at the point in the caller function where the throwing function was called. Should there be no caller, such as in the case of the main function or the initial function of a thread, the program or thread terminates.

- Exceptions are the preferred method for error handling in most modern languages. They have the principal advantages of preserving detailed information about the error that occurred and being difficult to accidentally ignore.

- One disadvantage of using exceptions is that they are relatively expensive to create and throw which can be a problem if the related error is relatively common, such as attempting to read past the end of a file. They also typically require special language support for throwing them, which rules out their use in simpler languages like C.

- Some languages such as Java additionally have the notion of a checked exception. When a function throws a checked exception, it is required to declare the type of the exception in its signature. When a caller tries to invoke a function that declares a checked exception in its signature, the compiler enforces that the caller actually handles the exception - either with an exception handler or by delegating to a higher-level function.

- It is challenging to design APIs that use checked exceptions since they propagate virally through function declarations. I will probably write a future article that specifically deals with using checked exceptions effectively.

- Some statically typed languages like Haskell implement the semantics of checked exceptions using a datatype such as

Either. Compilers in such languages enforce that callers explicitly unpack theEithervalue and handle any contained exception object explicitly.

- An exception is an object that encapsulates information about an error. This includes not only the type of error but also additional contextual information that can be used to generate a reasonable error message and assist in debugging by an end-user or developer.

In summary:

- Exceptions should be used for most error reporting needs.

- Error sentinels should be used to report common errors where the performance penalty of exceptions is too much.

- Error codes should be avoided entirely unless the programming language does not support exceptions, in which case error codes should be used instead.

Error Seriousness

Often the seriousness of an error is related to how it is handled. Generally speaking, errors are either:

- Common

- For example reading past the end of a file falls into this category, as it will always happen (once) whenever a program attempts to read an entire file into memory.

Very few errors fall into this category.

- Expected

- These errors are likely to occur in normal operation, but not commonly.

I/O errors related to reading from a file or from a network socket are an example.

- Unexpected

- Unexpected errors are ones for which the programmer did not plan any explicit handling.

This includes dividing by zero, dereferencing a null pointer, attempting to access an object off the end of an array, reading from a file that was closed, and other “programmer errors”.

- Fatal

- Fatal errors are a rare and particularly nasty subset of unexpected errors for which there is no good recovery strategy. Such errors almost always terminate the program when they occur.

- Fatal errors include running out of memory2, the inability to locate a method or library which the program was linked against, and other nasty conditions.

Common errors are typically reported using error sentinels or error codes for performance reasons. Other error categories are usually reported using exceptions unless the language in use doesn’t support exceptions, in which case error codes are used instead.

The standard libraries of programming languages typically distinguish between expected, unexpected, and fatal errors by using different exception base classes for each. This makes it easy to write exception handlers that can catch all thrown exceptions in a particular category. For example:

Java uses

Erroras the base class for fatal errors,RuntimeExceptionfor unexpected errors, and all other subclasses ofExceptionfor expected errors.C# uses

SystemException(informally) as the base class for unexpected and fatal errors. All other subclasses ofExceptionare used for expected errors.3Python uses

StandardError(informally) as the base class for unexpected and fatal errors. All other subclasses ofExceptionare used for expected errors.4

If a language supports checked exceptions, the expected exceptions should generally be marked as checked to force callers to handle them appropriately. Conversely, unexpected and fatal exceptions should not be marked as checked since this burdens the caller unnecessarily.5

Guarantees after Failure

When an error occurs in the middle of multi-step function, the function has to make a decision about what kind of state it wants to leave the program in when it returns to its caller. In general a function can leave the program:

- in its original state,

- This usually involves rolling back or reversing any actions performed prior to the error.

Functions that make this guarantee are called atomic or transactional.

- in a different but valid state, or

If a full rollback is not possible, it is still usually possible to partially rollback to a valid state.

- in a different and potentially illegal state.

- Naive functions may simply return immediately upon error, leaving whatever resources they were using in a bad state.

- This is particularly a problem for programs that use exceptions for error handling, as the default behavior when an exception is thrown is to return immediately, without performing any cleanup.

Any complex fault-tolerant function should document which of these guarantees it makes.6 If it makes no guarantees at all, the caller may have to assume that whatever resource the function was operating on is in a bad state if the function returns an error.

Consider the concrete example of a program that copies a comma-separated-value (CSV) file to a new file. This generally involves the steps:

- Open the source CSV file.

- Open the destination file, replacing any previously existing file.

- Loop over each row (or byte) of the source CSV file and write each row to the destination.

- Close the destination file.

- Close the source file.

Here is a naive implementation that makes no guarantees to its caller in the event of an error.

/** Copies the source CSV file to the destination file. */

// (I didn't think about error handling at all.)

public static void copyCsvFile(File sourceFile, File destFile) throws IOException {

InputStream fileIn = new FileInputStream(sourceFile);

OutputStream fileOut = new FileOutputStream(destFile);

int b;

while ((b = fileIn.read()) != -1) {

fileOut.write(b);

}

fileOut.close();

fileIn.close();

}

Now imagine what happens if an I/O error occurs in the middle of copying bytes: The write method will throw an IOException and since copyCsvFile has no matching exception handler, the copyCsvFile function itself will stop and rethrow the IOException. Notably, the destination file is left with incomplete and invalid CSV contents. And neither the source nor the destination file is closed, leaking those resources from the operating system.

We can at least avoid leaking resources by adding logic that ensures that resources are always closed when the function completes:

/** Copies the source CSV file to the destination file. */

// (No open file handles will be leaked even in the event of an error.)

public static void copyCsvFile(File sourceFile, File destFile) throws IOException {

InputStream fileIn = new FileInputStream(sourceFile);

try {

OutputStream fileOut = new FileOutputStream(destFile);

try {

int b;

while ((b = fileIn.read()) != -1) {

fileOut.write(b);

}

fileOut.flush();

} finally {

try {

fileOut.close();

} catch (IOException e) {

// Ignore I/O errors upon close since nothing can be done

}

}

} finally {

try {

fileIn.close();

} catch (IOException e) {

// Ignore I/O errors upon close since nothing can be done

}

}

}

This improved function will no longer leak open file handles in the event of an error but it will still leave an invalid destination CSV file.

If we document the additional guarantee that the function performs an atomic file copy, we’d want to explicitly code the function to delete the destination file in the event that it couldn’t be fully copied. Here’s an implementation:

/** Copies the source CSV file to the destination file atomically. */

public static void copyCsvFile(File sourceFile, File destFile) throws IOException {

InputStream fileIn = new FileInputStream(sourceFile);

try {

OutputStream fileOut = new FileOutputStream(destFile);

boolean finishedCopying = false;

try {

int b;

while ((b = fileIn.read()) != -1) {

fileOut.write(b);

}

fileOut.flush();

finishedCopying = true;

} finally {

try {

fileOut.close();

} catch (IOException e) {

// Ignore I/O errors upon close since nothing can be done

}

if (!finishedCopying) {

boolean deleteSuccess = destFile.delete();

// If the delete fails then the rollback failed.

// Since there's nothing that can be done in that case,

// we ignore deletion failures.

}

}

} finally {

try {

fileIn.close();

} catch (IOException e) {

// Ignore I/O errors upon close since nothing can be done

}

}

}

If we wanted to get even more fancy we could document instead that the function guarantees that it will copy as much of the source CSV file to the destination CSV file, leaving the longest valid destination CSV file even in the case of an error. In particular if the entire file cannot be copied, the function will copy as many complete lines from the source CSV file as possible, stripping off any incompletely written lines.

This is actually relatively difficult to implement correctly in Java while still handling characters correctly and preserving end-of-line sequences, so here’s a Python 2 implementation instead:

def copy_csv_file(source_filepath, dest_filepath):

"""

Copies the source CSV file to the destination file.

If an error occurs while copying, as many rows as possible are copied,

leaving a valid destination CSV file.

"""

with open(source_filepath, 'rb') as file_in:

offset_to_last_line_written = 0

finished_copying = False

file_out = open(dest_filepath, 'wb')

try:

while True:

cur_line_bytes = file_in.readline()

file_out.write(cur_line_bytes)

offset_to_last_line_written = file_out.tell()

file_out.flush()

finished_copying = True

finally:

truncated_successfully = False

if not finished_copying:

try:

file_out.truncate(offset_to_last_line_written)

truncated_successfully = True

except IOError:

# Unable to truncate. Will try to delete the file instead...

pass

try:

file_out.close()

finally:

if not finished_copying and not truncated_successfully:

try:

os.remove(dest_filepath)

except IOError:

# Unable to truncate or remove the destination file.

# Nothing else can be done.

pass

Actually the preceding implementation isn’t correct in the presence of output stream buffering (unless it is line-buffered), since it could be the case that the offset_to_last_line_written points to the end of a line that in fact has not been written to disk but is rather in the output buffer. A correct and performant implementation that additionally handles that case is left as a (non-trivial) exercise for the reader.

Failing Fast and Error Locality

Errors are easiest to handle when they are signaled at the exact point where a problem first occurred, or as close to it as possible. Thus functions should try to fail fast whenever possible.

It is a good idea for functions to check their inputs (especially their arguments) immediately upon invocation to see whether they conform to the expected format. This provides early warning of state corruption that could get introduced into the derived output of the function.

In addition if there are points where a function can make a non-trivial assertion about its current state, and this assertion is at risk of breaking due to modifications by maintainers, it should make an explicit check that the assertion is true.

assert vs. if

When checking assertions, a function can always use the humble if statement:

public class Registry {

private Map<String, Object> items = new LinkedHashMap<String, Object>();

public void register(String id, Object item) {

if (id == null)

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"Cannot register an item with a null ID.");

if (item == null)

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"Cannot register a null item with ID \"" + id + "\".");

if (items.containsKey(id))

throw new IllegalStateException(

"Already have an item registered with the ID \"" + id + "\".");

items.put(id, item);

}

// (... more methods ...)

}

However there is also an assert statement in many languages. The assert statement typically differs from if in that it can be compiled-out of the program automatically if desired, for a modest performance boost at the expense of safety. Therefore assert should typically only be used in performance-critical code (that has been verified as such by a profiler).

In practice I almost never use assert, preferring to rely on if instead.

Implementation Considerations for Exceptions

Exceptions are API

Expected exceptions7 are part of a function’s API. Consequently:

Expected exceptions should be given the same coverage in a function’s documentation as its parameters or return type. Remembering to document expected exceptions is particularly important when writing API documentation for languages lacking checked exceptions (i.e. everything other than Java, including C#).

Callers may depend on the expected exceptions in the function’s API documentation.

A function cannot remove or change the exceptions it throws without breaking callers that have been coded to expect the old set of exceptions. And new exceptions that are added will not be expected by existing callers.

Designing Exception Hierarchies

It is generally a good idea have a separate exception type for each specific type of error that a caller might want to handle distinctly. That way a caller can easily write an exception handler that catches a specific exception of interest. For example FileNotFoundException is likely to be treated distinctly from a generic IOException, so it is given a separate exception type (that inherits from the generic IOException class).

Errors that are not likely to be handled distinctly by the caller can just reuse a generic exception class directly. For example a piece of code that detected a “bad media” error when reading from a disk could just throw a plain IOException with a message instead of creating a special subclass. However note that by doing this you provide no API for any caller that does in fact want to catch this kind of exception.8

Designing Error Messages

An error message typically accompanies an exception, and it is this message that is typically presented verbatim to the user if high-level code doesn’t recognize the exception type itself. Therefore it is important that the message be:

- well-formatted,

- Therefore basic grammar rules apply, such as beginning sentences with a capital letter and ending them with a period.

A surprising number of real-world exception messages don’t even meet this low bar.

- understandable by the user,

- This is a tricky requirement because the point where an exception is generated may not know the kind of user that will eventually receive the exception, particularly if it is a low-level error that is deeply buried or if the error occurs in a widely-used utility function.

- In general expected errors are likely to reach a normal non-programmer end-user, so they should be written with that audience in mind.

By constrast unexpected and fatal errors are typically programmer errors and only likely to be seen by other developers when developing a program. Therefore they should be written with the developer in mind.

- specific, and

- An error message without sufficient contextual information cannot be easily corrected by the person that receives it. Messages should contain enough information for the user to easily locate the problem and fix it themselves.

For example a error encountered while parsing a text file should include information about the location of the parse error, so that the user can find the problem in the original document. Any good compiler will give you at least a line number when it encounters a syntax error and may even provide a specific column number as well.

- in the correct spoken language.

- In particular if the user’s current locale is non-English (such as German), a German message should be presented if possible, not a default English one.

- Programs that are only intended to be used in a single locale can ignore this guideline and naively emit messages in the expected locale’s language.

Translating Exceptions During Handling

Wrapping Low-Level Exceptions in High-Level Exceptions

It is common for a single system to have a single high-level exception type that is thrown by most of its functions. For example a parser’s functions may all throw the high-level ParseException.

However the implementation of such a system may delegate to other systems that use a different set of exceptions. In the case of a parser, it typically has to read the characters it is parsing from an I/O stream, which may throw a low-level IOException.

Now, top-level parser functions have a few options in reporting the underlying IOException as a possible failure case to its caller:

- Expose - The top-level function declares that it throws both

ParseExceptionandIOException.- However this exposes the implementation detail that the parsing system relies on the I/O system and forces the caller to deal with the low-level

IOExceptiondirectly. Therefore this is not generally recommended for top-level functions, although it may be used by internal functions.

- However this exposes the implementation detail that the parsing system relies on the I/O system and forces the caller to deal with the low-level

- Wrap - The top-level function intercepts

IOExceptions and translates them to a genericParseExceptionthat wraps the originalIOException.- This allows the top-level parsing functions to present the simpler exception API of just throwing a

ParseException. Callers of the parser remain able to intercept and extract the underlying

IOExceptionif they wish.

- This allows the top-level parsing functions to present the simpler exception API of just throwing a

- Map - The top-level function intercepts

IOExceptions and maps them to a special subclass ofParseException(likeParseIOException), optionally wrapping the originalIOExceptionfor further inspection by the caller.- This is similar to the “wrapping” approach, but makes it even easier for the caller to catch the underlying exception since it can directly catch the mapped exception (

ParseIOException). - Thus this approach is preferable if the underlying failure case is sufficiently important to advertise prominently in the exception API.

- This is similar to the “wrapping” approach, but makes it even easier for the caller to catch the underlying exception since it can directly catch the mapped exception (

In summary, most low-level level exceptions should be wrapped in the generic high-level exception. For prominent low-level exceptions, they should be mapped to a specific high-level exception subclass.

Here’s a Java example of a parser taking the “wrapping” approach to low-level I/O exceptions.

// The top-level methods of this class all throw ParseException in their API.

public class RuleParser {

public static Rule parse(InputStream input) throws ParseException {

try {

return new RuleParser(input).readRule();

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new ParseException("I/O error while parsing rule.", e);

}

}

private Rule readRule() throws ParseException, IOException {

// (...)

}

// (...)

}

Wrapping Error Codes in Exceptions

Sometimes a high-level function using exceptions needs to report an error received from a low-level function that uses error codes. In this case the low-level error code needs to be communicated to the caller somehow via an exception.

Typically the low-level function comes from an overall subsystem of some kind which uses error codes in general for error reporting. In such a case it is typical to define a generic exception to wrap all error codes received from the subsystem. This generic exception should preserve the original error code for inspection by callers, along with whatever extra context may be available from the subsystem, typically just an error message.

For example Python uses the OSError exception to wrap error codes received from the underlying C library. It is populated with the error code received from the C errno global variable and the message received from the C function perror().

Now the high-level function may not want to report this kind of low-level subsystem exception directly, in which case the “wrap” or “map” technique discussed above in “Wrapping Low-Level Exceptions in High-Level Exceptions” should be used in addition.

Promoting Error Sentinels to Exceptions

Typically error sentinels are used to report common errors that are intended to be handled immediately by the caller. However if the caller cannot handle the error itself but needs to delegate to its second-order caller, it typically needs to promote the sentinel to an exception.

As an example, the end-of-stream condition when reading from a stream is generally considered to be a common error in Java. However a function that is parsing a data structure out of a stream does not expect an end-of-stream when it is in the middle of parsing a structure. Thus the parser wishes to report the end-of-stream condition to its caller as either an expected or unexpected error (depending on context), both of which require an exception.

public class BinaryInputStream extends FilterInputStream {

public BinaryInputStream(InputStream in) {

super(in);

}

public int readUInt8() throws IOException {

int b = this.read();

if (b == -1) {

throw new EOFException("Unexpected end of stream.");

}

return b;

}

public int readUInt16() throws IOException {

return

(readUInt8() << 8) |

(readUInt8() << 0);

}

}

In the preceding example the -1 error sentinel was promoted to an EOFException.

Avoid Using Error Codes in Generic Exceptions

The use of internal error codes within a generic exception class should generally be avoided, since this makes it difficult to handle them. (One exception to this guideline is when using an exception to wrap external error codes received from another subsystem, as described above in “Wrapping External Error Codes in Exceptions”.)

Consider the following example:

// A generic exception that wraps its own set of error codes. DON'T DO THIS.

public class FetchException extends RuntimeException {

private int code;

private String text;

public static final int JOB_NOTREADY = 1;

public static final int TIMEOUT = 2;

public static final int AMBIGUOUS_NAME = 3;

FetchException(int code, String text) {

super(text);

this.code = code;

this.text = text;

}

public int getCode() {

return code;

}

public String getText() {

return text;

}

}

If you actually wanted to detect the JOB_NOTREADY case, you’d have to write code like:

public Job fetchJob(String jobName) {

for (int triesLeft = MAX_FETCH_ATTEMPTS; triesLeft > 0; triesLeft--) {

try {

return service.getJobs().get(jobName);

} catch (FetchException e) {

if (e.getCode() == FetchException.JOB_NOTREADY) {

// Retry again

continue;

} else {

throw e;

}

}

}

throw new FetchException(TIMEOUT,

"Job \"" + jobName + "\" was not ready after " +

MAX_FETCH_ATTEMPTS + " fetch attempts.");

}

It’s not pleasant having to put that if-statement in the exception handler. And the throwing of the TIMEOUT-coded FetchException couldn’t save contextual information like the jobName and MAX_FETCH_ATTEMPTS in a machine-readable field since the generic FetchException didn’t have fields that were specific to the TIMEOUT code.

A better solution would be to use specific subclasses of FetchException instead:

public class FetchException extends RuntimeException { ... }

public class JobNotReadyException extends FetchException { ... }

public class FetchTimeoutException extends FetchException {

private String jobName;

private int numFetchAttempts;

FetchTimeoutException(String jobName, int numFetchAttempts) {

super("Job \"" + jobName + "\" was not ready after " +

MAX_FETCH_ATTEMPTS + " fetch attempts.");

this.jobName = jobName;

this.numFetchAttempts = numFetchAttempts;

}

// (... Accessors for jobName and numFetchAttempts ...)

}

public class AmbiguousNameException extends FetchException { ... }

Then the code could be simplified to just read:

public Job fetchJob(String jobName) {

for (int triesLeft = MAX_FETCH_ATTEMPTS; triesLeft > 0; triesLeft--) {

try {

return service.getJobs().get(jobName);

} catch (JobNotReadyException e) {

// Retry again

continue;

}

}

throw new FetchTimeoutException(jobName, MAX_FETCH_ATTEMPTS);

}

Avoid Using Exceptions for Flow Control

Sometimes programs report common errors in the form of an exception instead of using a more appropriate mechanism such as an error sentinel. This is inefficient since throwing exceptions is slow in the common case. And it is awkward for the caller who must have an explicit exception handler around every invocation to deal with the common case. Don’t do it.

Using Exceptions for Thread Termination

However one case where exceptions are useful as a means of flow control is to force (or recommend) that a thread terminate. Such exceptions are classified as fatal errors so that most exception handlers ignore them.

For example Java uses the ThreadDeath exception (a subclass of the fatal Error) to terminate a thread. And Python uses the KeyboardInterrupt exception (a subclass of the fatal BaseException) to kill the main thread when the user presses Control-C.

Summary

Error handling is hard. But you’ll provide a better experience by properly handling and communicating errors back the user.

Don’t be that guy who provides useless generic error messages:

(I doubt even the program itself knows what went wrong.)

Related Articles

- Error handling styles in programming

Summarizes the most prominent strategies for handling runtime errors.

- Abandonment vs. Unchecked Exceptions for Error Handling

- Describes abandonment, an uncommon error-handling style.

Series

This article is part of the Programming for Perfectionists series.

-

Flawed functions that return sentinel values that are actually valid place extra onus on the caller to perform additional checks to determine whether an error actually occurred. For example PHP’s

stream_get_contentsfunction can return''orFALSEupon failure. But it can also return''upon success. See my insane workaround.↩ -

Most programs treat out-of-memory errors as fatal, although there are a few hardened programs like SQLite that treat out-of-memory as an expected error.↩

-

The C# exception hierarchy is illustrated in “C# exception hierarchy”.↩

-

The Python exception hierarchy is documented in “Exception Hierarchy”.↩

-

Java has a few annoying examples where unexpected exceptions were marked as checked, burdening all subsequent callers. In particular

Object.clone()throws the checkedCloneNotSupportedException, making it hard to use. And Java’s reflection library throws the checkedIllegalAccessExceptionandInvocationTargetExceptionwhenever you try toinvoke()a method, neither of which are expected errors. AndThread.sleep()throws the checkedInterruptedException. NowIOException, thrown by all I/O functions, is legitimately a checked exception because it is an expected exception.↩ -

Instead of documenting the guarantees after failure for individual functions, it also common to document an overall failure handling strategy for the entire system. For example most databases are documented as generally operating in a transactional fashion, with failed operations leaving the database in its original state. Of course some functions may deviate from the general policy, in which case the deviation should be documented.↩

-

Unexpected and fatal exceptions, on the other hand, are not typically part of a function’s API. As such, callers should not write exception handlers that depend on them.↩

-

In this circumstance a caller is forced to guess the exception type by parsing the exception’s message. However this solution is brittle since the message isn’t part of the API and could change in the future or vary depending on the current locale.↩